Women and Goddesses in Myth and Sacred Text: An Anthology, Tamara Agha-Jaffar, editor. New York: Pearson Longman, 2005.

Reviewed by Johanna H. Stuckey, Ph.D., York University, Toronto, Canada

When I was teaching Goddess courses in the 1970s to 1990s, I would have been really grateful to have had access to this textbook. It does what few other such books do: it provides key selections in translation from religious and mythical material pertaining to the goddess/woman being studied. Thus, students can dip into, among others, such works as the Babylonian creation story, the Hebrew and Christian Bibles, the Qur’an, and the Ramayana.

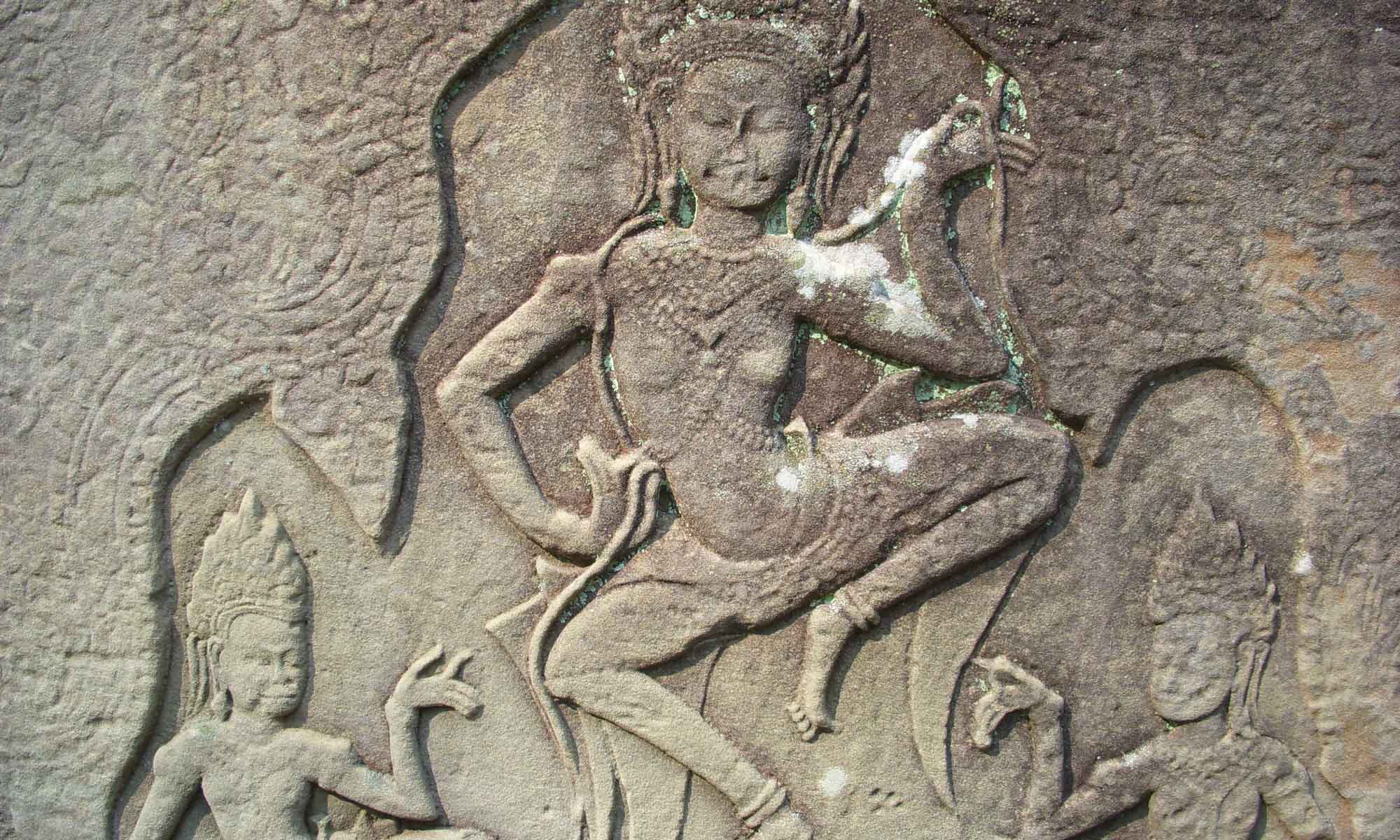

The goddesses and sacred women Agha-Jaffar treats are as follows: Isis, Inanna, Tiamat, Demeter and Persephone, Circe, Medea, Sita, Kali, Amaterasu, Kuan Yin, Lilith, Eve, Virgin Mary, Hawwa, Maryam, Oshun, White Buffalo Woman, and Corn Mother. If I had been picking the ones to include, I probably would have left out two of the sacred women (Circe and Medea) and added the Canaanite/Israelite Asherah and another Greek or Asian goddess or both. However, Agha-Jaffar’s choices reflect the course she was teaching and for which she devised this textbook.

For each goddess/woman, the author provides a glossary of names, a short background essay with bibliographical references and a family tree, where appropriate. Then she presents a selection from the most useful and comprehensive account of the goddess or woman. She ends each section with a list of questions for review and discussion.

For the Sumerian goddess Inanna, the selections come from the numerous poems about the courtship of the goddess and her “dying god” bridegroom Dumuzi followed by the full poem describing Inanna’s descent to the underworld and the short piece about Dumuzi’s becoming her substitute in the Great Below. For Demeter and Persephone she includes the whole Homeric hymn to Demeter, and for Medea Euripides’s play Medea. For Amaterasu, the selection is found in the oldest surviving book in Japanese, and for Kali it is excerpted from the long poem Devi-Mahatmya. Stories about Oshun, White Buffalo Woman, and Corn Mother derive from reliable collections of originally oral myths and legends.

Although I do have some criticisms of Agha-Jaffar’s choice of translations in areas for which I have some knowledge, nonetheless I have none with her choice of materials. The section on Lilith, for instance, focuses on the medieval Jewish Alphabet of Ben Sira, which retells the Lilith story in full. It represents the late development of the account of Lilith. Previously information on Lilith consisted of short Talmudic references to Eve’s predecessor. The Talmud’s two texts date to around 200 CE and 500 CE, making the Lilith story a quite late addition to Jewish mythology. There are no clear allusions to Lilith in the Hebrew Bible. Agha-Jaffar does not mention Lilith’s possible origin as a Babylonian air spirit.

This very useful and informative anthology covers a broad and representative range of world goddesses and sacred women and renders them in a scholarly, but accessible manner. It constitutes an important contribution to teaching and learning about the sacred female and is a valuable resource for Goddess studies.

Johanna E. Stuckey is Professor Emerita of Religious Studies and Women’s Studies, York University, Toronto, Canada.

One Reply to “Review: Textbook on Women and Goddesses”

Comments are closed.