Deity in Sisterhood: A Brief Introduction to the Collective Female Sacred in Germanic Europe

©2010, Dawn E. Work-MaKinne. All rights reserved.

Deae Matronae of the UbiPopular imagination often portrays pre-Christian Germanic religion as stereotypically patriarchal and violent. It is true that both pre-Christian and Christian Germanic religious expressions are principally male-centered, and much of the literature from the age of the Viking lore depicts the actions of violent men and families. However, alongside and within these stories, histories and religions runs a counter-view of the divine as collective and female. There are groups of goddesses and groups of female saints, often in collectives of three, but just as often unnumbered. Although it is not a requirement that collective deity be female, in Germanic Europe it is overwhelmingly the case. Collective goddesses and the collective female sacred can therefore be a subset of a larger concept, that of collective deity. For my purposes, collective deity is (1) a group of sacred or supernatural beings (2) collected under one group name (although they may carry additional individual names or epithets) (3) but not conflated into a single being; (4) worshipped collectively; (5) who act and wield their powers collectively and consensually.

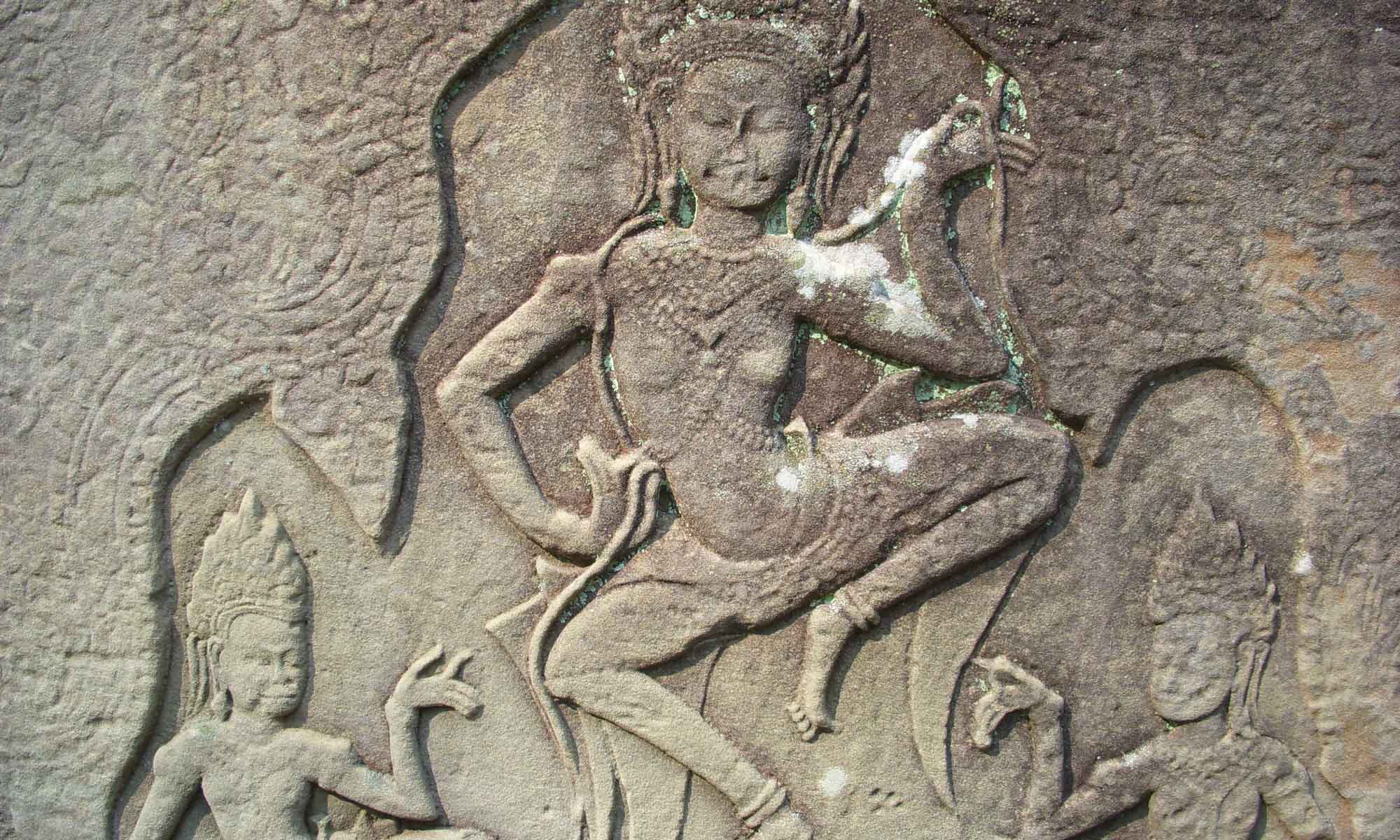

The collective sacred female is an underrecognized theme that winds through Germanic religious history, pre-Christian and Christian. The earliest example of the Germanic collective goddesses is the Deae Matronae, Roman-Celto-Germanic goddesses of the Roman Era Rhineland, at the beginning of the Common Era. These goddesses are always a threesome, and when they are depicted in artwork, show two goddesses with the large bonnet headdresses of the married Ubii tribeswoman, along with one goddess wearing the long, flowing hair of the unmarried Ubii woman. The artwork depicting the goddesses clusters around the century beginning 164 CE. Though the goddesses were those of a Germanic tribe, they were worshipped in a Roman manner, and the artifacts that remain are those carved by Roman stonecutters, remnants of the Roman vota ceremonies. The artifacts do not reveal the content of the vows fulfilled by the goddesses, but they do reveal the names and epithets of the Matronae goddesses: names speaking of the landscape, the peoples, the rivers, the animals and the bountiful nature of the goddesses.

It is almost a thousand years before the next collectives of goddesses appear in the Germanic historical record, and these are in Old Norse-speaking Iceland. Of the several collectives mentioned in their literature, perhaps the most important are the Norns, Norse collective goddesses of fate, and the Dísir, ancestresses, guardians and guides. Where the Matronae were goddesses connected closely with the landscape, the Norns and Dísir are collectives concerned with the life continuum, the arc of life from birth through love, battle, birth-giving and death. The Norns are sometimes a threesome, and sometimes unnumbered; the Dísir are always unnumbered. Old Norse pantheons are typically divided into the Æsir and Vanir deities, but the Norns and Dísir stand outside these pantheons, “half-goddesses,” belonging to neither and in ways more powerful than the full goddesses belonging to the Æsir and Vanir families. Their powers are more complex and complete, and in the case of the Norns, extend even over the gods.

At roughly the same time in the Middle Ages as the great flowering of Old Norse literature in Iceland, a collective of three female saints appears in the historical record in a village in Italy. This collective, called die drei heiligen Jungfrauen, or the Three Holy Maidens, is an example of a collective common in Germany, Austria, France and northern Italy. Like the Matronae, they are a group of three, and in this case they are literally sisters. This collective is not concerned with the life continuum so much as the work of protection, healing, help and succor. Some scholars think that the Jungfrauen collectives are a direct outgrowth of the Roman Era Matronae goddesses. Other scholars find a link between the Matronae and the Dísir. While there is some evidence of great age in the Christian Jungfrauen collectives, and also some evidence of pagan “Three Sisters” reverence continuing into the Christian era, it is very difficult to make a pronouncement on the issue of continuance between the various collectives, due to the great differences in time depth and geographic distances. Instead, it is useful to think of the collective sacred female in Germanic religious history as somewhat akin to a musical theme, with variations that occur in time and space. The collective sacred female is an overlooked theme in Germanic religious history, and provides an important corrective to simplistic views of the religious tradition as patriarchal and violent.

Bibliography

Bauchhenss, Gerhard, and Günter Neumann, eds. Matronen und Verwandte Gottheiten. Cologne: Rheinland-Verlag, 1987.

Burns, Vincent T. “Romanization and Acculturation: The Rhineland Matronae.” PhD diss., University of Wisconsin, 1994.

Gruber, Karl. Die Pfarrkirche von Meransen. Lana, Italy: Tappeiner Verlag, 1997.

Motz, Lotte. “Sister in the Cave: The Stature and the Function of the Female Figures of the Eddas.” Arkiv för Nordisk Filologi 95 (1980): 168-82.

The Poetic Edda. Translated by Lee M. Hollander, 2nd ed. Austin: University of Texas Press, 1986.

Work-MaKinne, Dawn E. “Deity in Sisterhood: The Collective Sacred Female in Germanic Europe.” Ph.D. diss., Union Institute and University, 2010.

My The Quest for the Nine Maidens Luath Press 2003, investigates one particular grouping in detail and found them not only in Europe but Africa, Asia and elsewhere.

Hello, Stuart,

Yes, I’ve read your book following the idea of the collective sacred female around the world. Really fascinating! Thanks for commenting. Dawn.